|

|

| author | books | poetry | about | audio/ site map | submit | Tea Leaves: mothers & daughters | links/contact | readings/appearances |

“There is something here for everyone who has ever loved someone else or plans to. I highly recommend “Tea Leaves” just because it is so real and so beautifully written.”–Reviews by Amos Lassen

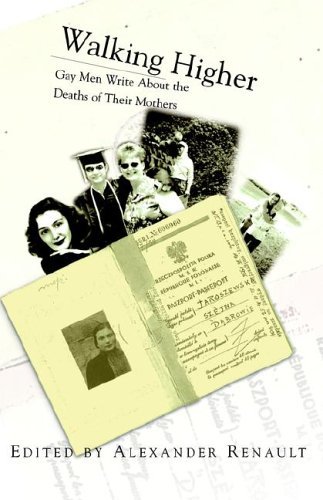

Walking

Higher: Gay Men Write About the Deaths of their Mothers

by Alexander Renault

This commentary was first aired on This Way Out, a worldwide lesbian and gay radio syndicate based in Los Angeles.

Click here to hear the audio review (mp3--5 MB)

Click here for a list of audio pieces/ site map

When a copy of the anthology Walking Higher: Gay Men Write About the Deaths of their Mothers (from Xlibris) first fell into my hands, I approached it with great interest and, I have to admit, with more than a little trepidation. I met the editor, Alexander Renault, after an readings/appearances event where we had both read at the gay, lesbian, and feminist bookstore Giovanni's Room. As we walked down city streets to the after party, he and I both shared stories about the deaths of our mothers and how his experience led to the creation of this compelling, moving, and insightful anthology.

In the introduction, Renault describes Walking Higher as a "collection

of 30 voices dedicated to exploring their relationships with the women who gave

them life, and managing the aftermath of their mothers' passing." The introduction

continues with, "Ten to twenty years ago, gay sons were pre-deceasing their

mothers in alarming numbers as out-of-sequence deaths from AIDS ravaged an entire

generation. Now that AIDS is a treatable disease, more gay men are surviving

their parents. Hence, it seems timely to offer a series of reflections on the

special and unique relationship of mothers and their gay sons from the perspective

of the surviving sons."

I was concerned that reading this anthology would bring back too many memories of facing my own mothers' death and, therefore, would be, in the vernacular of yesterday, "a downer." I was immediately drawn in to the collection and delighted to find out that in a few places the writing is absolutely hilarious.

In the collection's second piece, "My Glamorous Mother," Adam Jeffries

Schwartz, begins with "My mother is the most glamorous woman in the cancer

ward; her star quality is startling." After describing his mother as being

the center of attention in the private doctor's office in Manhattan where women

sit in recliners - a place that could be a spa if not for the "IVs full

of chemicals," he writes of his stay at his mother's and stepfather's house:

"I've been home for a month now. At first she looked as if she'd had the flu, tired but not seriously sick. Now, it's more than that. You have to remember, when your mother is as dedicated to youth as mine is, you never see signs of aging. I'd come home from college and she would look me over for signs of aging, which would reflect badly upon her. A few hours later I would counter strike.

"Mom," I'd say,

"Your eyes, again?"

"You're insane," she'd block.

"Mom, they turn up at the edges, like Barbara Eden's." She'd examine

her nails, so I would add. "Did you hear that Dad had his neck done?"

"No, I hadn't," she'd perk up. "What else?"

I am thirty-three, my parents fifty-four but in a science fiction kind of way.

I get older; they got re-modeled; the first sign of aging was this cancer which

will kill her."

Several of the contributors write about coming out-often in subtle ways-to their

mothers shortly before their deaths. Others, lament the fact that they were

not--for various reasons--able to come out to their mothers and wonder how things

could have been different between them.

This book challenges the definition and mores of masculinity where men are defined

by their ability to repress emotion. The collection also lends credence to the

notion that gay men are often very close to their mothers, but does so without

perpetuating stereotypes or romanticizing. In "Reason For Living,"

Sam Catalano writes about his experience growing up in "a post WWII Michigan

version of Levittown, just outside of Detroit," with his "classic

1950s stay-at-home mom."

"I think one of the great fears of gay baby boomers, and a major fear of

mine, was that our fathers would die and we would be the only ones left to take

care of our mothers. Since we couldn't marry and usually didn't have kids, it

was taken for granted that it would be our responsibility. That was certainly

one of my great fears given my father's history of heart attacks. I had heard

and seen so many stories of single gay men or lesbians having to care for an

elderly parent after the other parent dies. IN families in which all the children

have a house full of their own children, parents were often placed in nursing

homes. Not for the single gay guy. I often thought I would kills myself, or

my mother, if we had to live together for any extended period of time."

One of the greatest strengths of this anthology is its collective emotional

honesty, particularly in the revelation that for all of these men the deaths

of their mothers was a traumatic event and one that has left its scars. In Mama

Jane, Michael Hathaway writes about moving to St. John, Kansas to be near his

mother during the last three years of her life. The portrait that Hathaway paints

of himself and his mother is more of one of friends and colleagues. His mother

worked with Hathaway on his poetry magazine, the Chiron Review,

right up "through the week before her passing."

"I can't help being sad," Hathaway writes at the end of his essay.

"Missing her is the worst pain I've ever known. But I hold on to the joy

in having known her, having been so lucky to have been her child, her best friend,

and her partner in poetry."

In editor Alexander Renault's piece in the collection, The Hardest Part, he

writes about the aftermath of his mother's death when he checked himself in

to a mental health unit until he was sent home three days later. As a result

of his mother's death, Renault questioned every part of his life including his

relationship, his career, and his basic identity of who he was. A counselor

explained to him that, "after your mom dies the entire geography of your

reality is changed forever…Your self perceptions become bizarre. It is

as though you are standing in front of one of those distorting carnival mirrors."

As I read Walking Higher--regardless of where I was, on the bus, over lunch

in a crowded restaurant, and into the early hours as I read in bed--I continually

contemplated that fact that crying while reading is every bit as cathartic as

laughing.

| author | books | poetry | about | audio/ site map | submit | Tea Leaves: mothers & daughters | links/contact | readings/appearances |