| author | books | poetry | about | audio/ site map | submit | Tea Leaves: mothers & daughters | links/contacts | readings/appearances |

A classic becomes a classic because it survives the test of time.

Sappho became a classic because of her direct lineage to Homer, 200 years her senior, and for our collective memory of her as the first poet to openly express her lesbian desire on the page.

Gertrude Stein became a classic in part for her groundbreaking experimental literature and in part for her lesbian marriage to Alice (portrayed so compellingly in Stein's most commercially successful book The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, first published in 1933).

Radclyffe Hall's The Well of Loneliness, first published in 1928, became a classic because, as the first book to portray lesbian life and its accompanying oppression, it created an uproar on several continents.

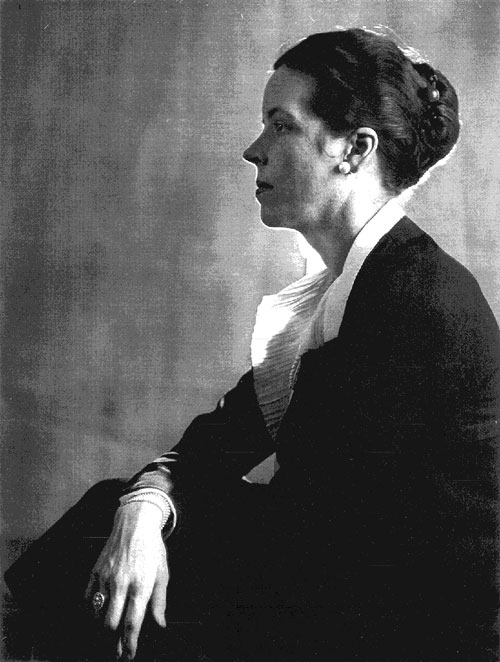

Writing at the same time as Radclyffe and Gertrude, Djuna Barnes gave us Nightwood, which on its first publication in 1936, was called an "underground classic" because of its edgy, experimental tale of the tragic places that love gone wrong can take someone.

It was published to little acclaim with reviewers calling it "strange and brilliant," "queer, morbid and interesting," and "The twilight of the abnormal," and yet it has stayed with us.

The bisexual Djuna Barnes wrote this book with the lesbianism of her characters, very much as an aside. There is no mention of the crime of society in its views toward two women in love: the crime lies in what two women in love are capable of doing to each other. And despite this fact, or perhaps because of it, Nightwood has stayed with us as a lesbian classic.

In

recent years, Nightwood has been republished by two different

publishing houses with introductions and prefaces with noteable lesbian literati

Dorothy Allison (Modern Library, in 2000) and Jeanette Winterson (New Directions,

in 2006).

In

recent years, Nightwood has been republished by two different

publishing houses with introductions and prefaces with noteable lesbian literati

Dorothy Allison (Modern Library, in 2000) and Jeanette Winterson (New Directions,

in 2006).

Like Gertrude, Djuna was another American expatriate who lived, in the 1920s and 30s, in the Left Bank of Paris, where they were both part of the same literary coterie. Although their artistic circles transcended both gender and sexual orientation, both Stein and Barnes were impressive constituents of what the critics of the time referred to (harkening back to the Sappho's golden city on Lesbos) as "The Mytilene elite."

It is said that art imitates life and this is certainly the case with Nightwood in which Djuna wrote about her heart breaking experience in her long-term relationship with the faithless artist Thelma Wood. In 1922, Djuna moved in with Thelma, who she would come to refer to as the "Great love of her life." Djuna longed for stability and monogamy but after a few idyllic years with Thelma remarked (bitterly one imagines) that Thelma wanted her "along with the rest of the world."

Thelma, who has an increasing dependence on alcohol, would leave their home and go from café to café and Djuna would follow. In Nightwood, Djuna turns Thelma into a character named Robin (in Robin there was this tragic longing to be kept, knowing herself astray) and elaborates:

"In the beginning, after Robin went away with Jenny to America, I searched for her in the ports. Not literally, in another way. Suffering is the decay of the heart: all that we have loved becomes 'forbidden' when we have not understood it all, as the pauper is the rudiment of the city, knowing something of the city, which the city, for its own destiny, wants to forget. So the lover must go against nature to find love. I sought Robin in Marseilles, in Tangier, in Naples, to understand her, to do away with my terror. I said to myself, I will do as she has done, I will love what she has loved, then I will find her again. At first it seemed that all I should have to do would be to become 'debauched' to find the girls that she had loved; but I found that they were only little girls that she had forgotten. I haunted the cafés where Robin had lived her nightlife. I drank with the men, I danced with the women, but all I new was that others had slept with my lover."

In real life, Djuna and Thelma lived together until 1928 when Thelma left to commence a relationship with the heiress Henriette McCrea Metcalf. In Nightwood, Djuna cast Henriette into the character of Jenny and wrote about her in excruciating detail:

Jenny Petherbridge was a widow, a middle-aged woman who had been married four times. Each husband had wasted away and died; she had been like a squirrel racing a wheel day and night in an endeavour to make them historical; they could not survive it.

She had a beaked head and the body, small, feeble, and ferrous, that somehow made one associate her with Judy; they did not go together. Only severed could any part of her have been called "right." There was a trembling ardour in her wrists and fingers as if she were suffering from some elaborate denial. She looked old, yet expectant of age; she seemed to be streaming in the vapours of someone else about to die….She was the master of the overly sweet phrase, the overly tight embrace…..

When she fell in love it was with a perfect fury of accumulated dishonesty; she became instantly a dealer in second-hand and therefore incalculable emotions As, from the solid archives of usage, she had stolen or appropriated the dignity of speech, so she appropriated the most passionate love that she knew, Nora's for Robin. She was a squatter by instinct.

Nightwood is not an easy read. It is peopled with numerous characters. In addition to the narrator, Nora, and Thelma; there is Jenny, the heiress; a transgendered doctor; an ex priest; and a Baron with whom Nora has long rambling philosophical conversations that spring from the vast wilderness of her heart. Nightwood is deeply Parisian and bohemian, in a setting with deeply iconic images--in one passage Nora likens herself to the Virgin Mother, waiting patiently for Robin to return.

It is tortured and complex but ultimately it remains a classic tale about a love so great that it is capable of stripping away the self. The question that Nora poses to her transgendered doctor friend, and ultimately, to the reader near the end of the book is:

"Have you ever loved someone and it became yourself?"

10-8-08

| author | books | poetry | about | audio/ site map | submit | Tea Leaves: mothers & daughters | links/contact | readings/appearances |